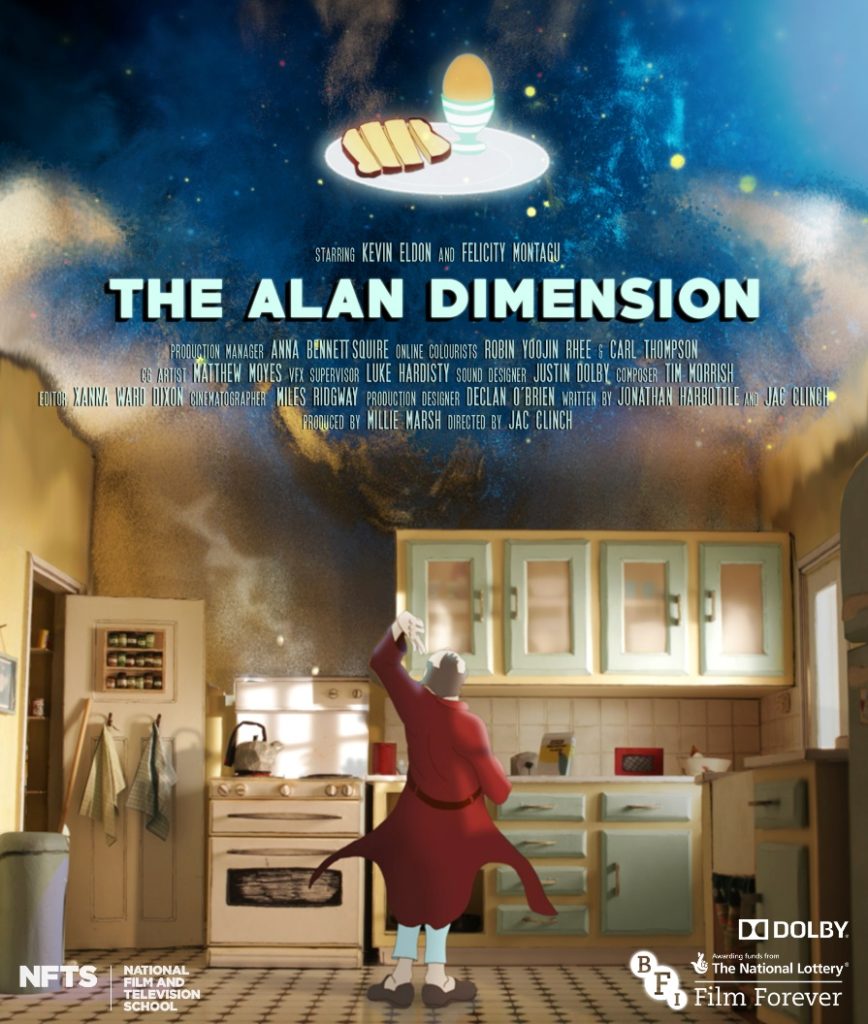

Much of the otherwise quiet life of Britain’s greatest landscape painter, Joseph Mallord William Turner, is coloured by extraordinary anecdotes. Turner was devoted to art making and it preoccupied the vast majority of his life, but there are only a few, disputed moments that can illustrate the wild, inventive passion evident in his work. In Rain, Steam and Speed – The Great Western Railway (1844), a train rushes obliquely from the turbulent elements, the almost synesthetic effect of which was apparently inspired by Turner sticking his head out of a window of a speeding train. Similarly, Snow Storm – Steam-Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth (1842) allegedly records Turner’s experience of being lashed to the mast of a ship in a storm.

|

|

JMW Turner

Rain, Steam, and Speed – The Great Western Railway 1844 support: 910 x 1218 mm

Oil paint on canvas

The National Gallery, London

|

Regardless as to the veracity of these stories, the paintings are indisputable – combining a mastery of his medium, oil, with an inventive genius. And perhaps even more remarkable than their mythologies, both works were painted when Turner was well into old age. While the Victorians regarded 60 as the start of a decline into senility, it was the start for Turner of his most remarkable, experimental and significant period in painting. It is this era, from 1835 to his death in 1851, which is celebrated in an exhibition at London’s Tate Britain – Late Turner: Painting Set Free.

The Tate Britain was made custodian of the Turner Bequest, the artist’s gift to the nation of around 30,000 works on paper and 300 paintings, after the artist’s death and it is this that forms the bulk of Late Turner. For visitors used to the extensive collection of Turner’s work that dominates the Clore Gallery of the institution, there are many familiar sights but also the exhibition is successful in bringing together significant works from across the UK and from around the world.

|

|

JMW Turner

Regulus 1828, reworked 1837

Oil paint on canvas

support: 895 x 1238 mm frame: 1135 x 1460 x 93 mm

painting

Tate. Accepted by the nation as part of the Turner Bequest 1856

|

Indeed, the sheer volume of art in the exhibition effectively conveys Turner’s industry in this period, the artist maintaining his exhibition record for oil painting each year, as well as his development in style and skill. Most

interesting in this regard is his Brighton Beach, with the Chain Pier in the Distance, from the West which was originally painted in 1827 but reworked in 1843. This sea scene, in its earliest form, can be seen to owe much to the Dutch seascapes which Turner admired – it is muted, expansive and light. In its reworking, Turner has played onto the matt surface expressive impasto, even using the end of his brush to enliven the surface. It not only reflects his increasing freedom in the medium but his increasing expression and energy in his painting.

The exhibition is notable for its presentation of Turner’s watercolours. These important and incredibly numerous works, often recording his tours around Europe which he continued to make until six years before his death, are often shown separate, and often as subordinate, to his oils. Here, however, they are given pride of place and rightly are considered not just as beautiful examples of Turner’s painterly practice, as his way of recording natural phenomenon, but as works in themselves. (Painting en plain air in oil did not become widespread until the invention of lead paint tubes in the 1870s). It was in watercolour that Turner first painted and arguably his liquid and translucent use of oil and his command of light, owes much to honing his skills in this watercolour. Venice: The Zitelle, Santa Maria della Salute, the Campanile and San Giorgio Maggiore from the Canale della Grazia (1840) exemplifies this, the colours as vibrant, tone as subtle and the detail as intricate and yet indistinct as his best work on canvas.

Late Turner is a fitting testament to the last years of Turner’s life, but it fails to identify why it was then that he reached the height of his art. His financial security, having found commercial success, meant that he no longer relied so much on commission and could paint with greater independence from his clients. But, more than that, it seems clear from his work, and from his contemporaries who would look with guilt at Turner’s incessant frantic sketching, that painting was Turner’s life. More perhaps than any other artist, it dominated his existence. That he produced his best work towards the end of his life is simply a result of the aggregation of seven decades of concerted, ceaseless work.

The final room of the exhibition is poignant. The eminent art critic, John Ruskin, believed Turner’s work declined after 1845 and these paintings are certainly the most indistinct and formless. This is largely in part to many being unfinished, an assessment that has only recently been made with these painting erroneously considered proto-abstraction in the 1960s. Welcomingly, the exhibition makes clear that these works would not have been shown by Turner but still they show Turner’s almost pagan love of nature where, as he is reputed to have said on his death-bed, “the sun is God”.

Late Turner: Painting Set Free runs until 25 January at Tate Britain, London