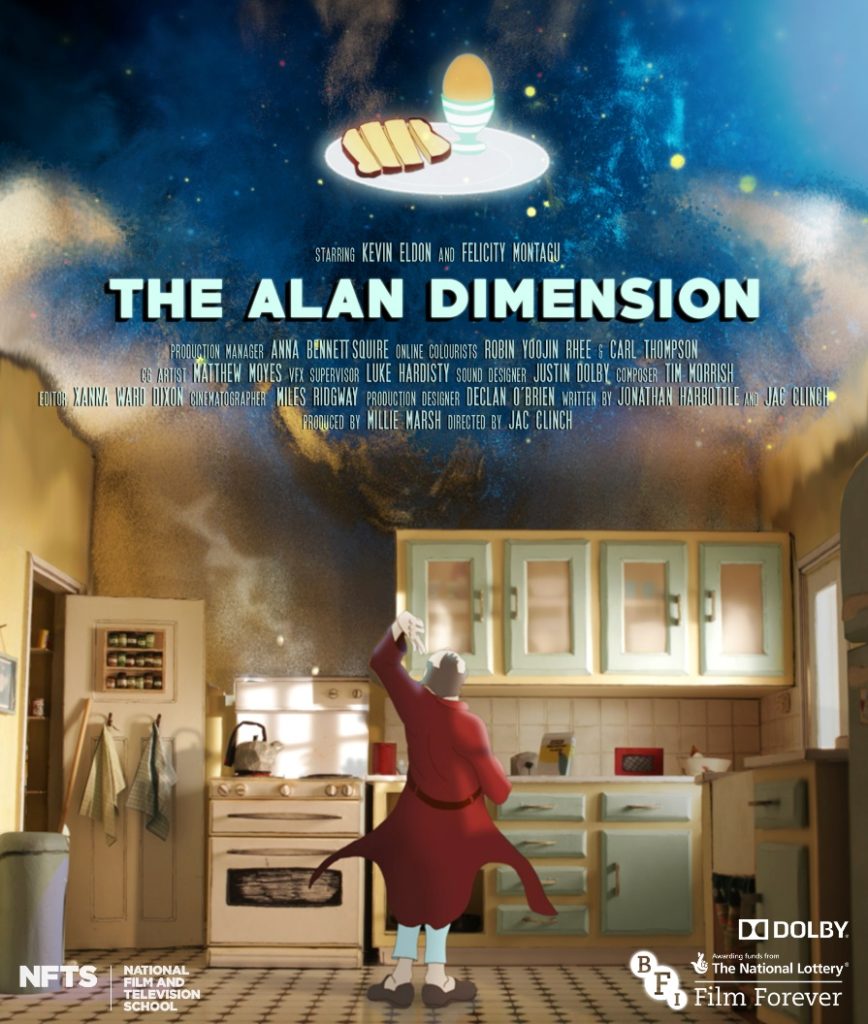

Director and animator Jac Clinch talks us through his creative process and the mainstays of animation. Nominated for a BAFTA, his critically acclaimed debut film “The Alan Dimension” is both funny and heart-warmingly earnest. He’s since garnered a reputation for his humour and has gone on to work for clients such as the Gorillaz, Channel 4, and Sky. Taking us behind the scenes, we cover his love of illustration, animator heroes, and collaboration in filmmaking.

How did you get started in animation?

I’ve been drawing my whole life – growing up, I dreamed of being a cartoonist.

So, I was certain I was going to go down the illustration route; it wasn’t until I was on a joint illustration and animation degree that I realised I was an animator at heart. I found that animation was this amazing gift, where I could make my drawings talk to me. It’s this magic spell that gives life to static characters.

They’re very much of the same family, but I would say that animation is more of a collaborative process. For example, there’s often a character designer whose illustrations are then brought to life by an animator.

There are also other members of the team. The director is responsible for the creative vision and the decision making, but there’s background artists, animators, clean-up artist, and then of course the producer who has the unenviable task of telling everyone how much money there is.

Each of these roles adds a new layer to the scene.

In animation it’s like you’re an actor in the film. You’re given a script but then how you interpret it is up to you. It’s an indirect performance, but you really get a sense of the animator from their work. Some people are really terrific at effects like clouds and explosions, while other do character animation, within which there is a whole spectrum of styles – from cartoony to nuanced realistic animation.

I think I’m quite firmly in the cartoony end of the spectrum.

Makes sense if you wanted to be a cartoonist.

Absolutely, the person I really learnt to animate from was Richard Williams. He’s famous in animation for the “The Animator’s Survival Kit” and first introduced me to rubber band animation. You might have come across it in early Mickey Mouse cartoons where all the limbs are bouncing and bending. Williams achieves the same flow, but without taking it so far that the joints read as broken. Every action is announced – slightly exaggerated – which I really enjoy.

In a lot of today’s animation education, concepts come first and the craft and tech second; the actual realisation of the idea is prioritised. So, it was Williams who taught me the nuts and bolts of animating a scene.

As you also work as a director, is that where you believe the concept first approach comes into its own?

In my current career I swap between director and animator roles – I take pleasure in both. Directing you are the visionary at the top who is making all the decision and evaluating the performances of the animators. You are the auteur, so yes, its very concept based.

But I think more and more, there’s fun to be had with the techniques of animation, you can convey different things with animation that are hard to signpost in live action. You can even go directly into a character’s internal world and bring in psychological realism.

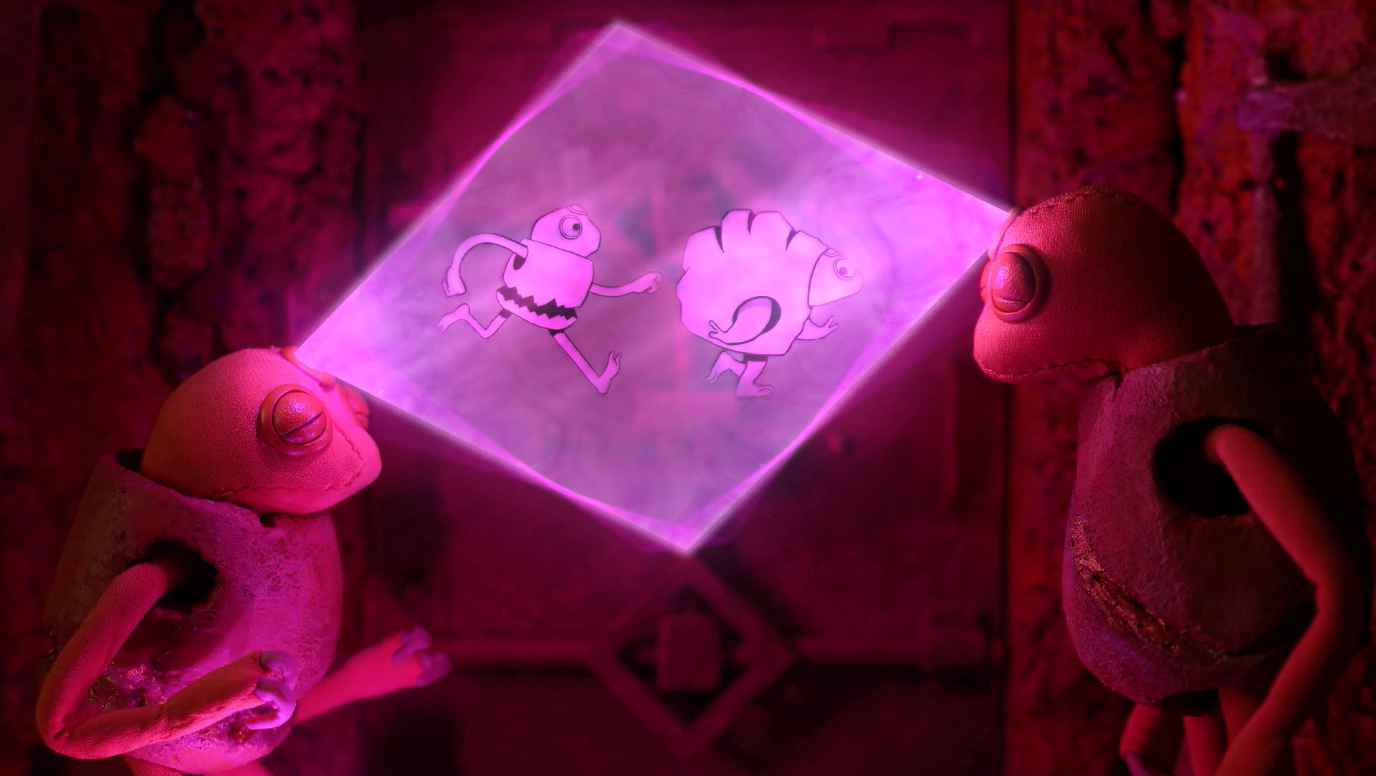

It’s a marvellous way of describing the inner thoughts. I collaborated with the director Astrid Goldsmith (who does stop motion animated films) in her film “Red Rover”. It’s about rock creatures that live on mars, and while there is no dialogue the characters are able to communicate by beaming their thoughts to each other. They shoot these beams out of their third eye, for which I created a 2D animation. Astrid and I focused on how these different characters with their different outlooks would think, and how this should affect how we animated their thoughts.

One character had a rosy outlook on life, so their thoughts were bouncy, fun, Mickey Mouse like, or more correctly “rubber hose animation”. Another character – who thought that everything was terrible – though in these angular looming shapes. I think it’s genius, and a way to give flavour to the mind’s inner workings that goes beyond what you can achieve in any other medium.