Anselm Kiefer was born in 1945 as the dust settled from Hitler’s rubble strewn Reich. Kiefer never knew the War and yet in the largest exhibition of the artist’s work in the UK, currently exhibited at the Royal Academy of Arts, there is a sense of the devastated, defeated, guilt ridden landscape of Germany after surrender. Through painting, sculpture and books, Kiefer has attempted to come to terms with his national identity by exploring Nazi symbolism and mythology and confronting the uncomfortable reality of the Nazi regime.

The colossal, breathtaking Ash Flower (approximately 4 metres by 7 metres) is perhaps the best example of this. Characteristically for Kiefer, oil is combined with emulsion and acrylic, clay and earth, ash and sand, and has been aggregated on the canvas over a period of 15 years (1983-1997). The painting is dense with impasto, almost to the extent of hiding, as in a degraded photograph, the scene depicted behind – a long vertiginous perspective down the wide high-ceilinged hall of a building. Specifically, the building is the Mosaic Room of the Reich Chancellery in Berlin, designed by Hitler’s architect Albert Speer. The muted palate, earthy but also evoking the degradation of copper, shows the building as a ruin; the impasto paint accumulated at the bottom of the work having decomposed into cracked earth. The dilapidated space, empty but for the melange of paint and a long sunflower, dried and bisecting the work, speaks of the faded glories and dreams of Nazi Germany – dreams that despite being universally vilified now were shared by the German people – and the hope of rebuilding from the ashes.

Kiefer’s unflinching confrontation of Germany’s recent and, to many Germans, unpalatable history has seen him branded as a neo-Nazi. But in an early photograph, for example, a man silhouetted against the sea raising his arm in a Nazi salute (reprised in a painting, Heroic Symbol V (1970)), does not glorify the Nazis but decontextualises it from images of crowds of obedient people and instead impassively presents the machinery of the dictatorship. This interest is reflected in his attic series, empty lofts where Kiefer would paint, commenting on the mythologised history that qualified much of the Nazi’s racially based ideology.

Kiefer also draws heavily on poetry, especially that of Paul Celan. Margarete (1981) was inspired by Celan’s Death Fugue in which the poet draws on his experience in a concentration camp and focuses on the titular character, a German prison guard and Shulamith, a prisoner. In the painting, strange, three dimensional organic structures grow out of the earth, at once evoking the blonde hair of Margarete (they are made of straw) and the barbed wire that she guards. The earth from which they grow are the ashes of Shulamith’s hair. The straw is topped with the flames of the furnace.

Although not all his work is fixated on the rise and fall and aftermath of the National Socialist Party, throughout the RA show there is a rich darkness, a fertile gloom that evokes the terrible guilt Kiefer and other Germans have inherited. Perhaps because he is liberated in not having lived through the war, or perhaps out of his strength of character, Kiefer manages to directly confront the machinery through which the German people become complicit, unknowingly or otherwise, in the Nazi regime and the atrocities it committed. His work is a bold, composed and considered view of a country, a people and the artist himself rebuilding not just a land devastated by war but a nationality, devastated by fanaticism and dictatorship.

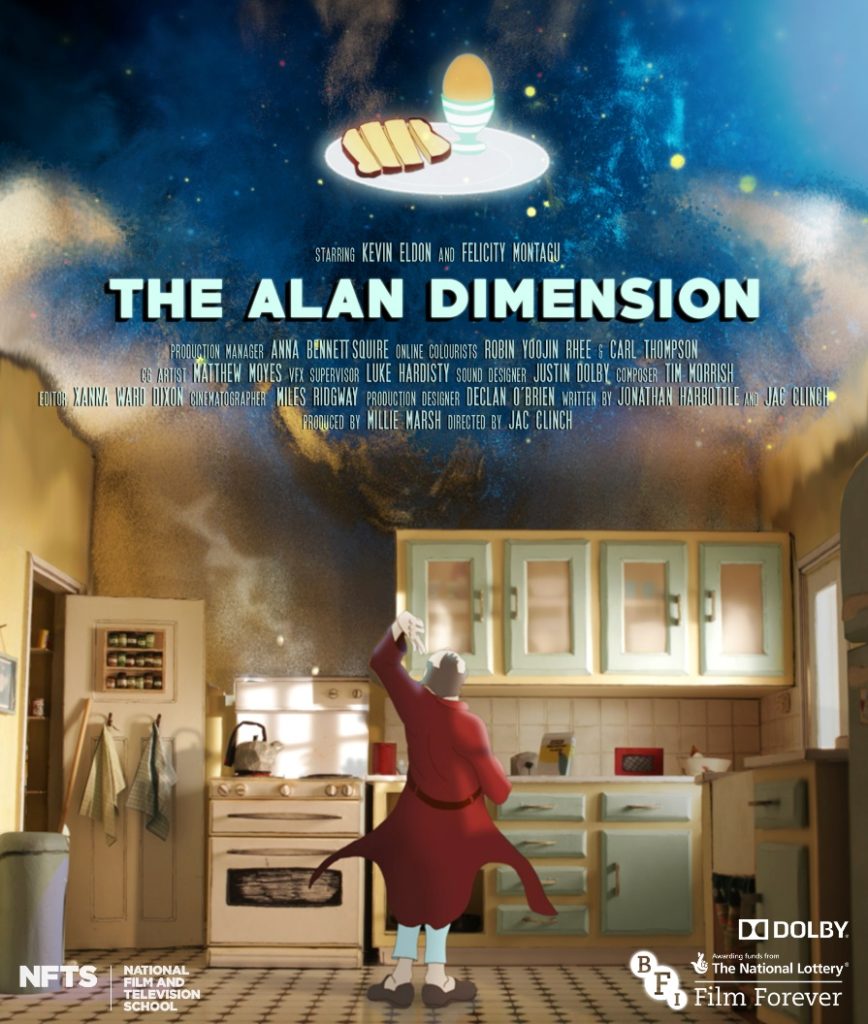

Images shown are of the courtyard of the Royal Academy and the vitrines made by Kiefer for the exhibitions.

Anselm Kiefer runs until 14th December at the Royal Academy of Arts, Piccadilly, London.