“I paint because colour is a significant language to me.”

Georgia O’Keeffe’s retrospective at Tate Modern coincides with the much-anticipated Switch House extension, but has independently attracted thousands of summer visitors. It is perhaps because the great American modernist gave a voice to those influential female artists overlooked during the twentieth century. Curated by Tanya Barson, the exhibition brings together six decades of O’Keeffe’s work; from 1915-63. Supported by the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in Santa Fe, New Mexico the retrospective presents 221 objects from paintings and sketchbooks, to iconic photographs by Ansel Adams, Alfred Stieglitz and Paul Strand.

Born to dairy farmers in Sun Prairie, Wisconsin, O’Keeffe went on to study at the Arts Students League, New York. From 1916 she became involved with the photographer Alfred Stieglitz, who she later married. Her early charcoal drawings were exhibited in his iconic Gallery 291 – a nostalgic space cleverly evoked by the décor of the retrospective’s opening room. But past those first charcoals lie the gifted colourist’s abstractions like the seascape Abstraction – Alexius (1928). O’Keeffe read Kandinsky’s Concerning the Spiritual in Art and explored the relation between form, music, colour and composition with paintings.

Painting aside, I appreciated the focus on O’Keeffe’s friendships within the Stieglitz group and the ‘optimistic cultural nationalism’ they embodied in New York. In competition with a male-dominated art scene, she decidedly re-claimed the urban space with linear works like New York Street with Moon (1925). Contrasting O’Keeffe’s architectural works, I was moved by the intimacy of the nude photographs Stieglitz took of his lover. Georgia O’Keeffe Breasts (1919) is a powerful expression of her sexuality and interestingly it was he who suggested an underlying eroticism in her work – despite her displeasure at critics gendering her art.

Critics assumed works like Grey Lines with Black, Blue and Yellow (1923) were representative of female genitalia, encapsulating femininity. O’Keeffe dispelled these assumptions stating that, “when people read erotic symbols into my paintings, they’re really talking about their own affairs.” In painting flowers she considered her purpose to be a re-engagement with nature rather than an expression of her sexuality. In reference to those blooms, she declared, “I’ll make even busy New Yorkers take time to see what I see of flowers.” O’Keeffe also played with scale, magnifying subjects like the fiery bloom of Oriental Poppies (1972).

O’Keeffe’s abstractions are often described as an experience of something, rather than the object itself. However, her style reverted to an almost photographic realism in works like Jimson Weed/White Flower No.1 (1932), as she dispelled the sexualisation of her work. This painting being the most expensive ever sold at auction by a female artist when it was bought for £34.2m in 2014. O’Keeffe’s engagement with nature continued with Oak Leaves, Pink and Grey (1929). Despite her protestations one can’t help but see a sensuality in the curvature of the leaves. But rather than casting her as a feminist icon, the curator respected O’Keeffe’s denial that her work is erotic.

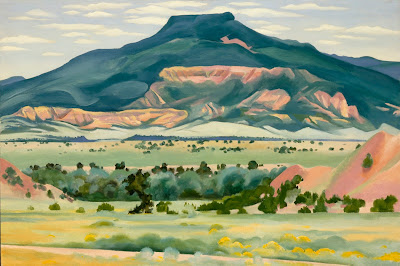

Ever the pioneering spirit, O’Keeffe explored her beloved New Mexico alongside artists like Marsden Hartley and the photographer Ansel Adams. She created a body of work inspired by those Southwest landscapes known for the calming, subdued palettes she channeled in Ranchos Church New Mexico (1930-1). Oddly there’s nothing haunting about the sun-bleached skulls in From the Faraway, Nearby 1937 or Horses Skull with Pink Rose 1931, because she sees life in them. Again, O’Keeffe subverts expectations, because they aren’t symbolic of death.

O’Keeffe’s retrospective was long overdue. In fact, the celebration of a female modernist’s work is long overdue. Whilst decidedly overlooking the suggestion of eroticism in her work, the curators illustrated her unique balance between the figurative and abstraction. Although her paintings lack textural distinction, they are rich in colour and atmosphere. O’Keeffe survived two world wars and 17 Presidents, never failing to whole-heartedly embrace her surrounding landscape; from New York to New Mexico – a lifetime beautifully captured by Tate Modern.

Written by Flora Alexandra Ogilvy, founder of Arteviste.com