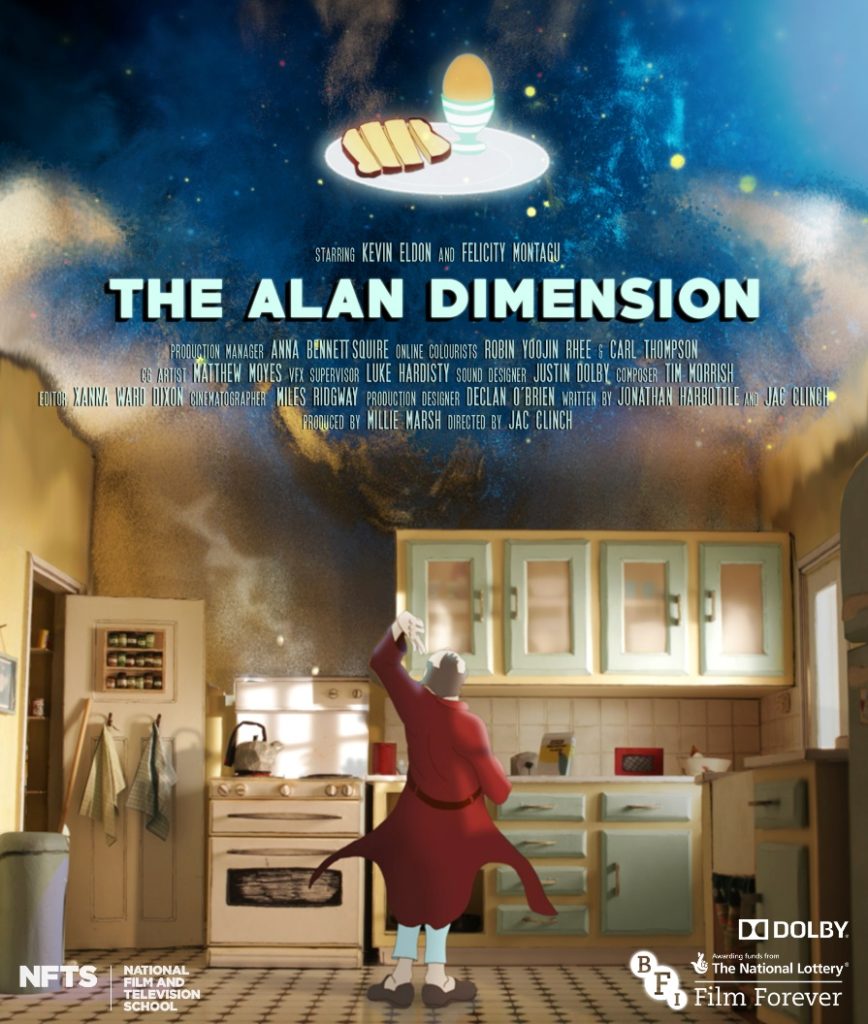

Defined as the voice of a generation, the American photographer Nan Goldin is known for capturing the most intimate experiences of her friends and lovers across Boston and downtown New York. At the Museum of Modern Art in New York, a slideshow of her iconic collection of images The Ballad of Sexual Dependency compiles nearly 700 photographs. Much of it is shot with only available light between 1979 and 1986 amidst the hard-drug subculture of the Bowery neighbourhood. Although the exhibition begins with an assemblage of posters, flyers and photographs from the museum’s archive, it’s the gentle rhythm of The Velvet Underground’s All Tomorrow’s Parties in the screening room that makes you feel like you’ve walked into Goldin’s downtown apartment. Given the slideshow’s soundtrack, it’s unsurprising that Goldin’s early influences include Andy Warhol’s films shot just a decade before as his studio The Factory moved further and further downtown.

Named after Bertolt Brecht and Kurt Weill’s The Threepenny Opera, the series of 35mm photographs in The Ballad of Sexual Dependency depict love, drug-use, gender, sexuality and domesticity. When the collection of images was first shown, Goldin hand-picked slides as friends spontaneously chose the soundtrack and her subjects looked on spellbound. In 2016, The Ballad of Sexual Dependency has already been viewed by thousands of strangers, but feels no less intimate. As a girl who has spent much of her youth running around New York in the company of a diverse array of artists, musicians and photographers, taking my place in the audience felt like the end of pilgrimage or perhaps just an important stop along the way. Undoubtedly, this sentiment was also intensified by my recent audience with her erotic The Boy at the Art Angel takeover of HM Prison Reading in England.

As an opener, the title photograph Nan one month after being battered 1984 serves as a powerful reminder that her photographs explore the good, bad and the ugly. Not only does Goldin capture the romance of the last bohemia in downtown New York, but also the harsh realities of addiction, domestic abuse and the AIDS epidemic. She described The Ballad as, “my form of control over my life. It allows me to obsessively record every detail. It enables me to remember.” As we millennials move into the realm of hyphenated job titles and over-sharing our emotions and space, there’s no doubt that revealing our vulnerability is becoming an asset. As tear-stained, tired and often lacerated faces stare down from Goldin’s projected images, their honesty makes them feel like friends and it feels like Goldin was far ahead of her time in depicting their struggles for the world to see.

Across the image, my favourite photograph was Nan Goldin and Brian in Bed 1981 in which she watches her shirtless lover smoke a cigarette in the morning light, and I longed for it to arrive on the screen. Although, I knew what to wait for give that Goldin had vaguely organized the collection of photographs into loose themes such as intravenous drug use, couples on their way to parties, sexual encounters and portraits of the children born from those affairs. These images were all set against the backdrop of iconic songs like Screaming Jay Hawkins’s You Put Spell On Me, which, makes you feel as if you’re there dancing with her subjects. What is so unique about Goldin’s work is that her vibrant, colourful photographs are taken by a participant, not an observer. You feel what she feels. This gritty, “grunge” style has since been reflected in indie publications like Dazed & Confused and I-D.

The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is equal measure beauty and despair, and as the slideshow draws to a close there’s no doubt that death and loss have become prevalent themes. By the 1990’s, most of her subjects like Greer Lankton and Cookie Mueller were dead. Although Goldin admits to romanticising the image of drug culture in the early days, now she mournfully describes it as “evil.” She captured a time when her bohemian contemporaries longed for deeper feel and rarity and for those they were willing to risk everything. As she documented the highs and lows of her friends’ and lovers’ lives, Goldin was never afraid of showing the dark effects of their hedonism.

Personally, having documented my last decade in daily journal entries, reading Goldin’s declaration, “The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is the diary I let people read,” makes this exhibition feel like a necessity for every young woman negotiating the perils of life in the city. Take a couple of hours to experience it before February 12th2017, it might be the most important history lesson you ever take.

Nan Goldin: The Ballad of Sexual Dependency is at MoMa, New York until 12th February 2017