Before a friend suggested that we go to see his retrospective, I had never heard of Sigmar Poke. The extensive and comprehensive exhibition, just closed at the Tate Modern in London was, then, a welcome introduction to Polke and his work and, for an ex-Art Historian, I had the uncanny but not disagreeable experience of seeing a vast body of work fresh and unsullied by digital facsimiles. It was a small window into life pre-Internet, and I throughly enjoyed it.

However, unenlightened but curious, perhaps I was exactly who the Tate is aiming at. For the most visited museum in the world, the Tate Modern is surely conscious that its visitors are not all art literate and that many are drawn by the spectacle of the converted power station’s architecture and the sensational, large scale Turbine Hall installations. Indeed, as I began to walk around the exhibition, I did not notice my lack of preparatory research or prior knowledge of Polke. Picking up what information I needed from the wall panels and the booklet guide, I could drift, drawn from one work to another, following the whim of my fancy.

|

|

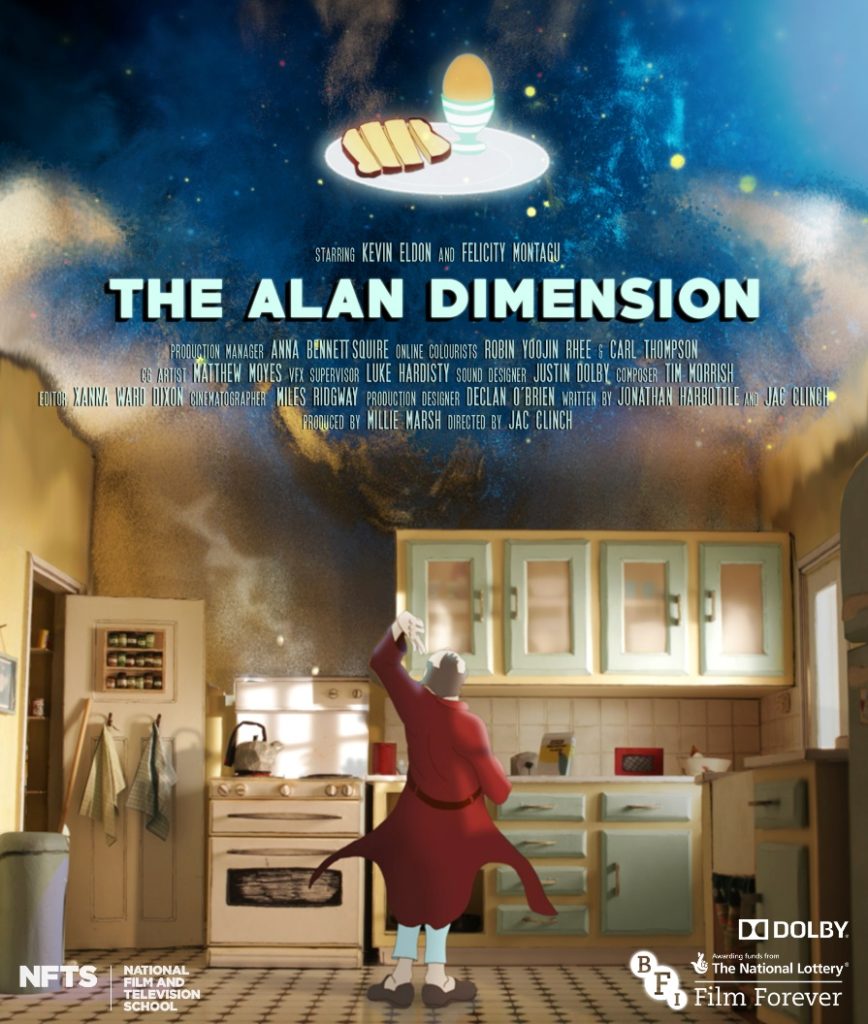

Sigmar Polke (1941 – 2010)

Girlfriends (Freundinnen) 1965/66

© 2014 Estate of Sigmar Polke / ARS, New York / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

|

The relatively sparse hang (the exhibition benefited by occupying an entire floor of the Tate Modern) accommodated this relaxed approach to Polke’s work. The succinct introduction was enough to let you start bringing your own conclusions to his work. The short biography, for example –

Born in Silesia in 1941, Polke had to leave his home with the advance of the Russian Army at the end of the Second World War. Again in 1953 he was displaced as his family fled East Germany to settle in Dusseldorf. He settled in Cologne in the late 1970s and died in 2010.

– immediately allows you to cast Girlfriends (1965-66) in its political and cultural context and interpret Polke’s anarchic take on popular imagery as a comment on the gaudy post-war Western consumerism that must have been startling to someone fleeing Communist East Germany.

Like many of his contemporaries – specifically Pop Artists in England and America – Polke was drawn to comment on the rise of consumerism and mass media. He decontextualised mundane food stuffs and used images found from newspapers and adverts. And yet, unlike Roy Lichtenstein, who also recreated mass printing methods in paint and Richard Prince, who similarly reappropriated mass imagery, there is something particular and more sophisticated about Polke. In the work above, the artist has mimicked by hand the raster printing process (an method of organising dots of colour to form an image) but, doing so by hand, there is a human and even humorous feel in the ensuing imperfections.

|

|

Sigmar Polke (1941 – 2010)

The Illusionist 2007

Private Collection

© The Estate of Sigmar Polke / DACS, London / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

|

And this sense of humour is present throughout the exhibition, tying together half a century of varied and disparate work. Police Pig (1986) is, at its most basic, very funny, and whether Polke is confronting Germany’s Nazi past or the non-Western cultures he encountered in his many journeys to Asia and South America, whether he is painting or taking photographs, there is this same wit imbued in everything he did. Although to look solely at these works for their humour is to over simplify them, it is this that gives him the edge on his fellow pop-commentating artists. This extra dimension serves to remind the onlooker that there are issues that need to be faced, discussions that need to be had, but that nothing should be taken to seriously.

|

|

Sigmar Polke (1941 – 2010)

Police Pig (Polizeischwein) 1986

© The Estate of Sigmar Polke / DACS, London / VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

|

To have such a vast collection of work from throughout Polke’s creative life allows the viewer to freely draw together his work from across the decades and visually come to these conclusions. Many retrospectives allow you to do this but it was especially present here. It is a testimony to the curation, of course, but also to this astoundingly talented artist – whatever he turned his hand to, in his sketches and in his films, in his paintings and sculpture, he got it just right. I had no knowledge of Sigmar Polke before I came to the exhibition but I left thinking he was one the best artists of the latter half of the 20th century.

.jpg)