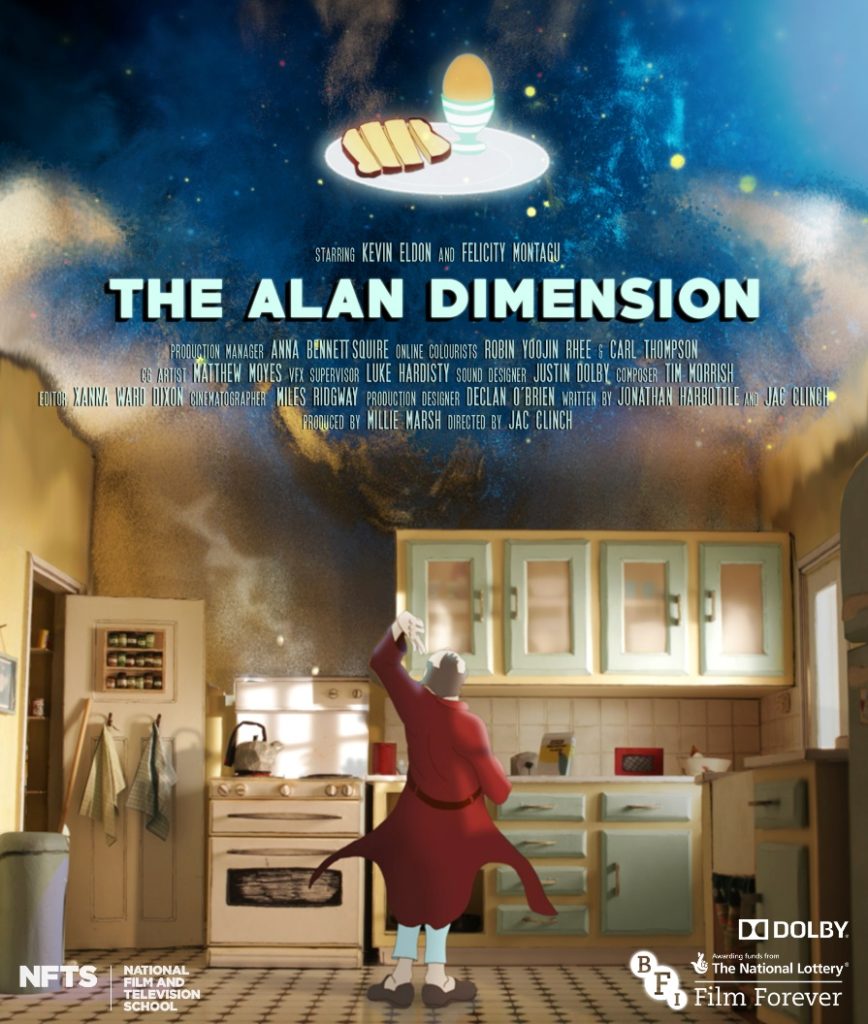

The work of Richard Diebenkorn defies simple classification – at once inheriting the tradition of Abstract Expressionism from his American compatriots and at the same time flirting with figuration, often on the same canvas. His paintings constantly question the nature and purpose of painting in a process that explores all aspects of art, what it is and what it will become. A concise and informative survey of the artist’s work at the Royal Academy of Art in London runs until 7th June. Its fittingly simple title – ‘Richard Diebenkorn’ – belies the artist’s uniquely inquisitive and experimental approach to art and art making.

Cityscape #1 from 1963 evokes the sun-bleached languor of California where Diebenkorn spent most of his life, the shadows stretching long at the end of the day. A nod to Cezanne in the work’s simplified flat plains and colour palette, here Diebenkorn toys with abstraction. After all, at first glance and when encountered at close range in a gallery space the painting, not overwhelmingly large but still sizeable enough to be reduced to unintelligible blocks of colour until you take a few steps back, is an abstracted reality. It is sanitised of the ephemera of street furniture, unpopulated, condensed down to an idyllic, idealised concept of a certain place and time.

And yet this work has none of the self assured, bold, uniform treatment of paint of his AbEx forbears such as Rothko or Hofmann, or even of his Cali-contemporaries such as David Hockney. For, once you have invaded the painting’s personal space, the forms of roads and condos not only break up into forms but the forms themselves disintegrate to reveal a rough, intensely worked surface, a gentle violence subsisting beneath the indolence and prosperity of suburban California.

Cityscape #1 is crucial as it anticipates a series of 125 paintings that Diebenkorn executed between 1967 and 1985, the last eight years before his death in 1993. The Ocean Park works carry through to a purer form of abstraction Diebenkorn’s soft, faded pastel colours, as if they have been left in the sun to discolour.

It would be easy to compare the Ocean Park series to Mondrian’s work – the thick white bands that break up the geometric, coloured forms, the vague evocation of a mechanised landscape, seem to acknowledge this precedent. But while Mondrian draws attention to the flatness of the canvas through a perfect uniform surface, denying the three-dimensional, liquid properties of paint, Diebenkorn makes a point of the materiality, the almost sculptural nature of painting. His works are riddled with pencil lines that show through painted regions that are not solid forms but fragile and translucent layers of suspended pigment, manipulated in an imprecise, essentially human manner.

As a result there is a depth and emotion to Diebenkorn’s paintings. As the painter and Royal Academician Ian McKeever observes there is a pregnant space, a sense of expectation that prefigures the conceptualisation of meaning throughout all of Diebenkorn’s work. The paintings are waiting for the indeterminate landscapes of abstracted place and time, first depopulated and rid of purpose, and now with form obliterated, to be reconstituted from the incoherent mass of pencil and paint. But ultimately Diebenkorn’s work is a celebration of painting, of the simple joy of applying paint to a freshly primed canvas.

|

| Richard Diebenkorn Berkeley #5, 1953 Oil on canvas, 134.6 x 134.6 cm Private collection Copyright 2014 The Richard Diebenkorn Foundation |