7th October – 10th January 2015

The Sackler Wing’s latest retrospective celebrates the revered artist Francisco Goya, a Spanish romantic painter who worked during the 18th and 19th centuries. A chronicler of his era, his portraits and wartime canvases are world-renowned. Goya captured the characters of his subjects, making no effort to beautify or embellish their appearances, which was unheard of at the time. Harking back to Keats’s declaration that, “beauty is truth, truth beauty,” his subjects’ personalities shine through, whether woeful or elated. Although, critics like Jeremy Paxman – in his ArtFund interview – have continued to debate whether Goya mocked or merely rendered his subjects true to form. There’s no doubt that every painting illustrates both technical skill and aesthetic concern, but I found there to be something awkward about the way he leaves each work, as if there’s something crucial missing. In comparison to his fellow Spaniard Velazquez’s retrospective in Paris this summer, I fear that Goya’s portraiture is somewhat inferior.

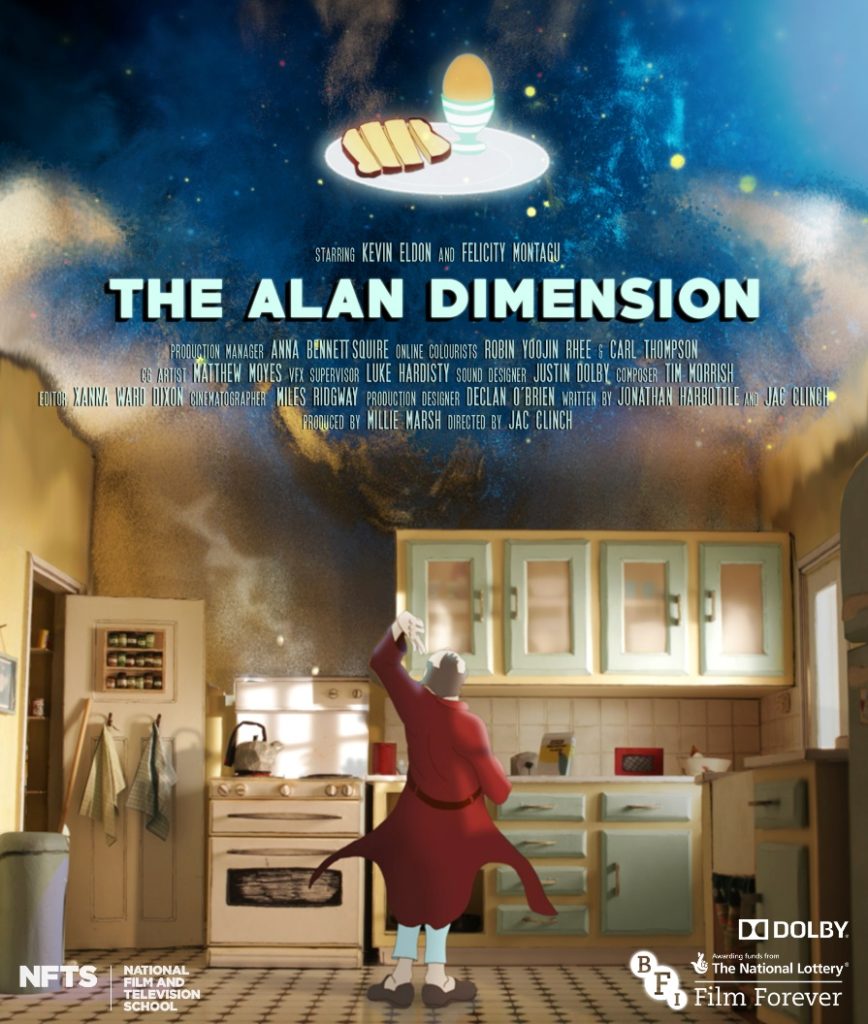

General Nicolas Philippe Guye, 1810

Walking from end to beginning to avoid the crowds, we were impressed by the National Gallery’s bold choice of Egyptian or prussian blue walls, which intensified Goya’s colour palette. Although we were soon to be underwhelmed by his portrait of Juan de Villanueva, 1800-5, which gave the impression of idleness as the shoulders sloped off into nihility. Only the sincerity in the popping buttons of the waistcoat gave it any sort of charm. We then encountered the ill-fated Ferdinand VII 1814-15 whose sartorial flare was defeated by his depiction as an intensely unattractive, stout little man. Although Paxman declared this to be representative of Goya’s negative feelings for Ferdinand, one wonders whether he was simply unattractive.

Of the liberals and despots, General Nicolas Philippe Guye, 1810 was the Adonis, who lifted the mood of the room. Not only was his bone structure particularly tempting, but his lavish uniform boasted an array of glittering decorations, which showed off Goya’s technical skill. As we moved through to the final rooms, I must admit that I rather liked the scripted underlying many of the portraits, which broke the illusion and made the paintings seem more textured.

Caspar Melchor de Jovellanos

Having interned in the auction houses, I tend to assume that amidst the Old Master works there is always a muse or scorned lover waiting in the wings. None so obvious as the exhibition’s centerpiece, the Duchess of Alba 1797, in which she gestures towards Goya’s name written in the sand, publically declaring her lust for him. Given the violent return of Spanish lace in the fashion world, one can’t help, but align this painting with the endless Dolce and Gobanna campaigns adorning all forms of public transport. It’s always interesting to connect contemporary design and Old Master paintings.

As we progressed to paintings of the Spanish Enlightenment, we were astonished by the sight of Caspar Melchor de Jovellanos’s expression of utter boredom in his docile portrait. How a subject could allow himself to be forever preserved in a moment of indigence, I do not know.

The Duke of Osuna’s portrait was far more captivating, because of the exquisite gradation from pthalo to cobalt blue, which was just as you imagine the sky to look as a child. We wandered past Goya’s ethereal portrait of the Duke and Duchess of Osuna, 1788 and their ghostly brood, questioning why the mother lacked any form of bone structure, but the children wore beautiful terraverde fabrics. It baffles me how the faces of so many of Goya’s portraits have faces painted like an afterthought, void of definition, but juxtaposing immensely detailed fabrics and jewels, which prove his capability. I’d recommend you go and see for yourselves, because although the National Gallery put on a well organized, beautifully presented show as always, I fear it was the works themselves, which let it down.

http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/whats-on/exhibitions/goya-portraits

By Flora Alexandra Ogilvy, founder of Arteviste.com