24 October 2015 to 31 January 2016.

There is no doubt that the Sackler Wing of the Royal Academy, London has enjoyed a year of distinguished exhibitions. With the retrospectives of the esteemed American artists Joseph Cornell and Richard Diebenkorn, the coveted space has reached new heights. As the leaves began to fall, I feared it was all over, but soon found myself deafened by whispers about the little known artist Jean-Etienne Liotard’s retrospective. Described by the Guardian as, “a joyous time machine back to the enlightenment,” the truly exquisite exhibition captures an age of revolution in time and thought.

Liotard was a Swiss-French painter, art dealer and connoisseur. Of his portraits, I was most intrigued by the very image, which haunted the underground’s walls throughout weeks of anticipation. The painting from the posters was his sumptuous work Woman on a Sofa Reading 1748-52, which depicts a young Turkish woman wearing a floral costume, adorned with luxurious fur and pearls. Reading a discussion of virtue written in French, she is a picture of elegance. Reflecting the exoticism, which so intoxicated 18th century France, turqueries may have been widespread, but Liotard’s commitment to ethnographic accuracy was unique.

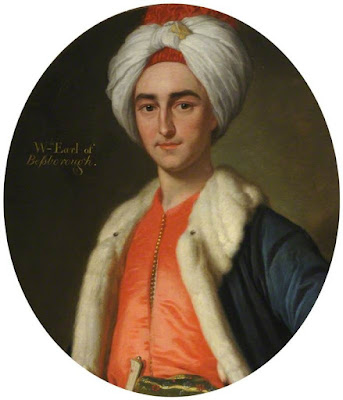

An artist of the Enlightenment period, his portraits reflect the spirit of curiousity and experimentation, which had swept through Europe at the time. When it came to choosing his subjects, Liotard immersed himself in the layers of European wealth and patronage, which supported him. This loyalty is captured in his decadent portrait of William Posonby, Viscount Duncannon, 1738 who had invited Liotard to join his glamorous travels between Rome and Constantinople. The famed intermediary between aristocratic sitters and painters is depicted wearing the Turkish costume he would wear to the Dilettanti Society’s meetings in London. Known for his ability to capture the nuances of his subject’s sartorial flare, Liotard was able to imitate the furs and extravagant embroidery, which his contemporaries were enslaved by.

Painting portraits for the French, Hapsburg and British Royal families, Liotard was well acquainted with the higher echelons of society. His delicate portrait of Princess Elizabeth Caroline, 1754 captures the fragility of a sickly child who memorised her parts in plays, because she was too weak to read. His ability to capture the temperament of his subjects with the subtlest facial expressions makes them all the more captivating. As my consort, the artist Piers Jackson declared, “Liotard’s characters are so real that you feel you could undo the bows around their necks.”

Before leaving, I returned to Liotard’s portrait of Madame Paul Girardot de Vermenoux, 1763, which perfectly blends genre painting and portraiture. The subject was famed for her beauty, but widowed young and so inherited a vast fortune, which allowed her to move freely in the expensive circles of Paris and Geneva. She is depicted as an allegory of the vestal Virgin in theatrical costume that pays homage to her doctor Tronchin who takes the role of the Greek God of medicine. Elaborate as ever, this portrait puts the Wallace Collection to shame.

Against the decadence of the works and drawings the subtle grey palette of the walls had a calming effect and complemented the space, but I fear that there weren’t quite enough works to fill it. Although, Liotard’s painterly skill and the sense of intimacy he creates between the viewer and subject certainly quench any thirst for both highly observant and opulent portraiture.

By Flora Alexandra Ogilvy, London-based art journalist and founder of Arteviste.com.